Research supported by the Center for Quantum Leaps advances the field of quantum simulation using an atomic-level quantum system.

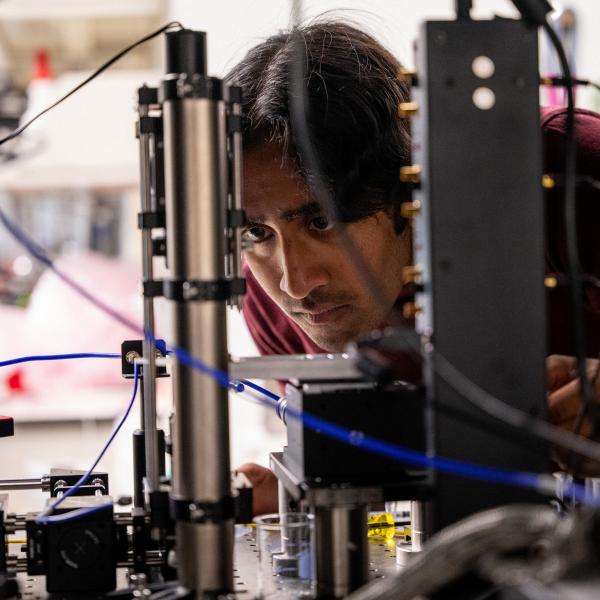

Diamonds are often prized for their flawless shine, but Chong Zu, assistant professor of physics, sees a deeper value in these natural crystals. As reported in Physical Review Letters — one of the most prestigious journals in the field of physics — Zu and his team have taken a major step forward in a quest to turn diamonds into a quantum simulator.

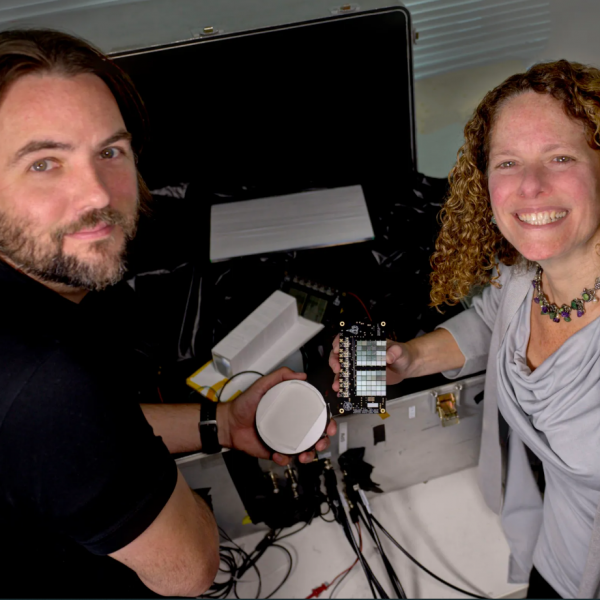

Co-authors of the paper include Kater Murch, professor of physics, and PhD students Guanghui He, Ruotian (Reginald) Gong, and Zhongyuan Liu. Their work is supported in part by the Center for Quantum Leaps, a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan that aims to apply quantum insights and technologies to physics, biomedical and life sciences, drug discovery, and other far-reaching fields.

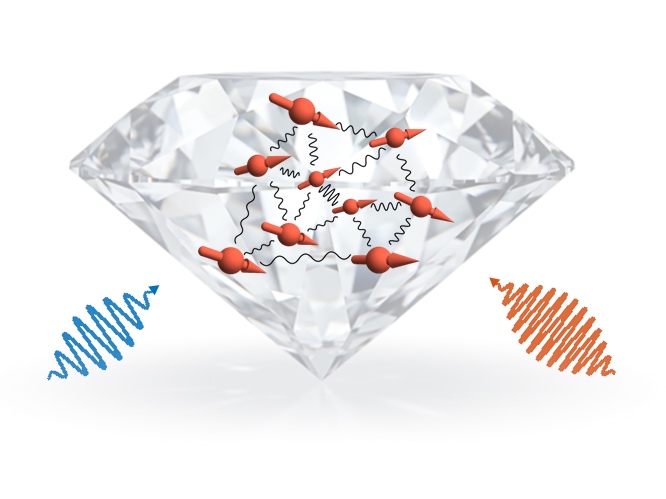

The researchers transformed diamonds by bombarding them with nitrogen atoms. Some of those nitrogen atoms dislodge carbon atoms, creating flaws in an otherwise perfect crystal. The resulting gaps are filled with electrons that have their own spin and magnetism, quantum properties that can be measured and manipulated for a wide range of applications.

As Zu and his team previously revealed through a study of boron, such flaws could potentially be used as quantum sensors that respond to their environment and to each other. In the new study, the researchers focused on another possibility: Using imperfect crystals to study the incredibly complicated quantum world.

Classical computers (including state-of-the-art supercomputers) are inadequate for simulating quantum systems, even those with just a dozen or so quantum particles. That’s because the dimensions of the quantum space grow exponentially with each particle that’s added. But the new study shows that it’s feasible to directly simulate complex quantum dynamics using a controllable quantum system. “We carefully engineer our quantum system to create a simulation program and let it run,” Zu said. “In the end, we observe the results. It’s something that would be almost impossible to solve using a classical computer.”

The team’s progress in this area will enable the investigation of some of the most exciting facets of many-body quantum physics, including the realization of novel phases of matter and the prediction of emergent phenomena from complex quantum systems.

In the latest study, Zu and his team were able to keep their system stable for up to up to 10 milliseconds, a long stretch of time in the quantum world. Remarkably, unlike other quantum simulation systems that operate at ultra-cold temperatures, their diamond-built system runs at room temperature.

One key to keeping a quantum system intact is preventing thermalization, the point at which the system absorbs so much energy that all of the flaws lose their unique quantum features and end up looking identical. The team found that they could delay this outcome by driving the system so quickly that it doesn’t have time to absorb energy. This leaves the system in a relatively stable state of “prethermalization.”

The new diamond-based system allows physicists to study interactions of multiple quantum regions at once. It also opens up the possibility for increasingly sensitive quantum sensors. “The longer a quantum system lives, the greater the sensitivity,” Zu said.

Zu and his team are currently collaborating with other WashU scientists in the Center for Quantum Leaps to gain new insights across disciplines. Within Arts & Sciences, Zu is working with Erik Henriksen, associate professor of physics, to improve sensor performance. He also plans to use them to better understand the quantum materials created in the lab of Sheng Ran, assistant professor of physics. He’s also collaborating with Philip Skemer, professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, to get an atomic-level view of magnetic fields in rock samples; and with Shankar Mukherji, assistant professor of physics, to image thermodynamics in living biological cells.