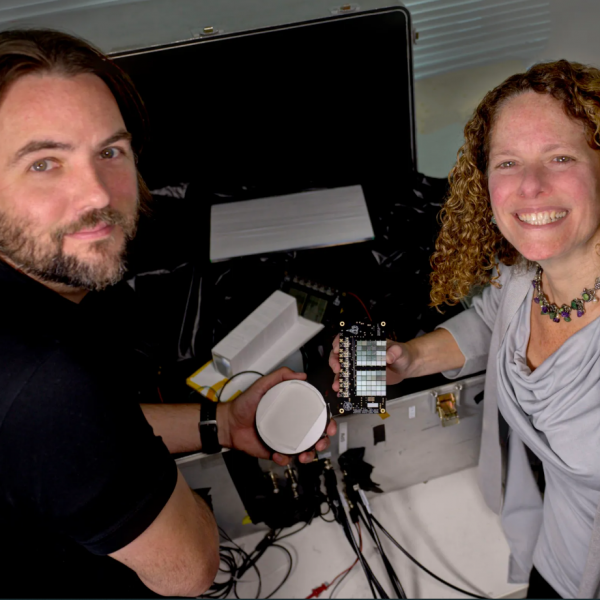

As part of the Center for Quantum Leaps, Chong Zu and colleagues study the quantum power of atomic flaws.

The most interesting parts of nature are often the imperfections. That’s especially true in quantum physics, the atomic-level world where tiny flaws can make a big difference in the ways particles behave and interact. As reported in a paper in Nature Communications, Chong Zu, assistant professor of physics, and his team are finding new ways to harness the quantum power of defects in otherwise flawless crystals.

The work is supported in part by the Center for Quantum Leaps, a signature initiative of the Arts & Sciences Strategic Plan that aims to apply quantum insights and technologies to physics, biomedical and life sciences, drug discovery, and other far-reaching fields.

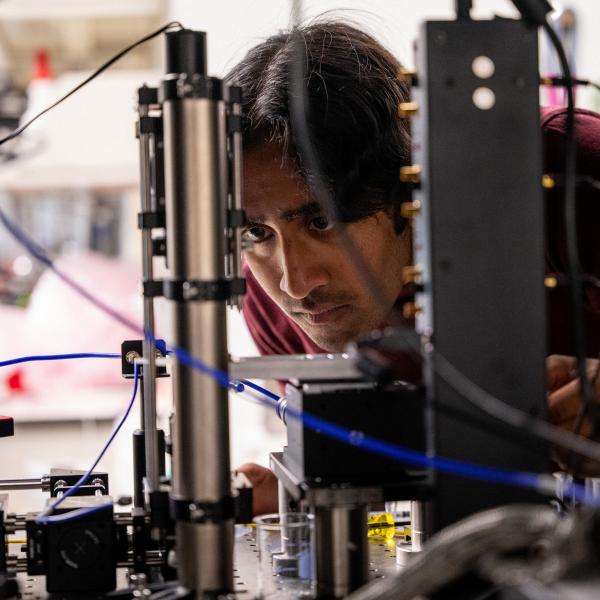

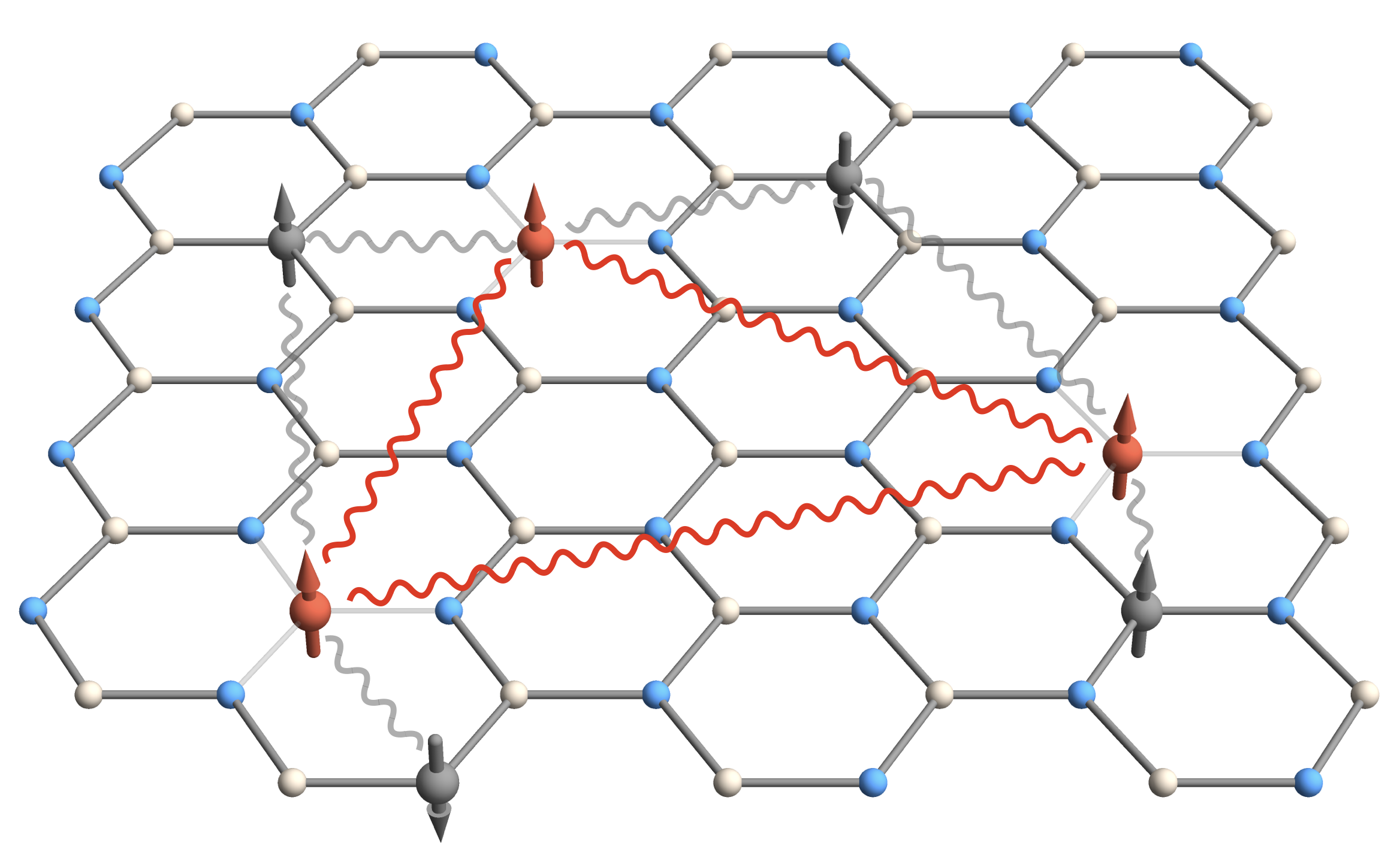

Zu’s lab is looking at atomic flaws in boron nitride, a material that forms sheets so thin it can be considered two-dimensional. Boron nitride is generally unchanging and uniform but, every once in a while, a missing boron atom will leave a tiny space. These gaps can happen naturally, but Zu and his team — including graduate student Ruotian (Reginald) Gong — sped up the process by bombarding microscopic flakes of the material with atoms of helium, little atomic bullets that randomly knock out boron atoms.

The resulting gaps have important quantum potential. The voids naturally fill with electrons that are highly sensitive to their surroundings. For example, tiny shifts in magnetic fields and temperature can change the spin and energy state of the electrons. This sensitivity makes them potentially useful as quantum sensors. In the new study, Zu, Gong, and colleagues showed for the first time that the electrons also react to changes in electric fields, expanding the range of potential applications.

Because these particular sensors are trapped in a thin, stable matrix of boron nitride, they could theoretically be applied to a wide variety of substances, from geologic to biologic. Other types of sensors are typically created in vacuum environment that must be chilled to temperatures near absolute zero. “You could never put something that cold next to a living cell,” Zu said. The sensors made from boron nitride, however, are room temperature.

The boron nitride sensors could be also used in basic simulation experiments to study quantum interactions of particles, Zu said. Physicists often use computer programs to predict how particles might interact, he said, but the systems are so complex that even the highest-powered computers can only work so fast. “Instead of trying to build the systems on a computer, you can just create the exact system that you want to study and then examine the interactions,” he said.

Zu and his team are currently collaborating with other WashU scientists in the Center for Quantum Leaps to gain new insights across disciplines. Within Arts & Sciences, Zu is working with Erik Henriksen, associate professor of physics, to improve performance of the sensors. He also plans to use them to better understand the quantum materials created in the lab of Sheng Ran, assistant professor of physics. He’s also collaborating with Philip Skemer, professor of Earth and planetary sciences, to get an atomic-level view of magnetic fields in rock samples, and with Shankar Mukherji, assistant professor of physics, to image thermodynamics in living biological cells.